Mandarin Chinese, like English, is a language full of different regional accents and slang. Within mainland China, these distinctions help to create soft in-group and out-group dynamics, dividing the North, South, East, and West and establishing a sense of regional identity. This concept holds true when discussing the Taiwanese accent but is further compounded by the current relationship between Taiwan and China.

At Wesleyan, all Mandarin textbooks for 1st-3rd year Chinese are published in Beijing. As such, within the language and grammar of the lessons, pieces of a Beijing dialect are codified and become second nature for new language learners, such as myself. Wesleyan does an excellent job of providing students with diverse perspectives and hiring language teachers and FLTAs from all over China and Taiwan. That said, first-year students are rarely well-informed enough about the power of language in geopolitics to go out of their way to deconstruct a codified Beijing accent, especially considering the difficulty posed by 1st year Mandarin courses, and often end up with a distinct regional accent.

I had never considered my Mandarin accent before my time in Taiwan from February through August 2023. The daunting task of surviving in a foreign and complex language overshadowed the nuance of how I sounded when I spoke. However, once I arrived in Taiwan, it became apparent that an accent like the one the Wesleyan textbooks teach is a surefire way to stick out negatively. My first exposure to this came during my interactions with my new Taiwanese roommates. I had asked where I could buy basic toiletries but ended my statement with an ”儿” (ěr), causing both of them to laugh. This harmless mistake did not cause any tension. Still, it made me question my Mandarin in a way I had never considered, a feat quite impressive considering I spend significant time second-guessing it.

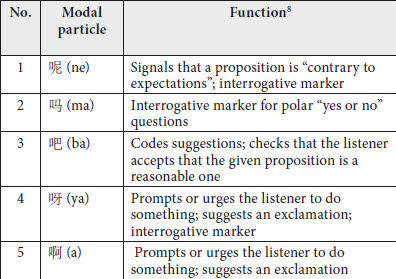

This sort of situation happened relatively frequently, where I said something with a Northern mainland accent and was met with laughter. In the classroom, since textbooks are still written to prepare students for the HSK (the standard Mandarin level test in Mainland China), the text’s elements of a Beijing accent were still codified. In this new setting, however, students would emphasize them for comedic effect or skip them altogether when they came up in class. Suddenly, if I wanted to blend in or begin to shed my out-group status, I found it necessary to drop the elements of my accent that were clearly Northern. In addition, new modal particles such as “啊”(a), “誒”(éi), “啦”(lā), and “嘍”(lóu) were taught during class specifically to replace our more northern (儿)(ěr) and (吧)(ba).

The accent switch became truly necessary when it came to specific politicized terms. For instance, in mainland China, Mandarin is called “普通话,” or the common language, while in Taiwan, it is called “國語,” or the national language. When traveling outside Taipei, people would ask me why I spoke Mandarin. The first time I answered this question, I said that proficiency in “普通话” (the mainland term) was a requirement for my major. The person I was speaking with was around 50 years old and was adamant I repeat the sentence, replacing the mainland term with the Taiwanese one. Once again, while it was not a significant issue, it left a lasting impression and got me thinking more about language power dynamics. If I were Taiwanese and had lived my entire life feeling financial and social pressure from mainland China, I, too, would be incredibly conscious and proud of my national identity. For the rest of my six months in Taiwan, intentionally and unintentionally, my Beijing accent slowly disappeared, replaced by a Taiwanese one.

Upon returning to campus, While my Mandarin was much more fluent, I once again had quirks that stood out in my language class. Specific phrases I had picked up, words I had switched out, and my spoken pacing were under scrutiny by my Mandarin teachers. This is not because they felt my accent was wrong, but because now, if I went to mainland China, I would be identifying myself as someone who had studied in Taiwan, which can be dangerous. I have not consciously tried to change my accent to a Beijing one again, but I have noticed elements creeping in. When I speak on the phone with my old roommates, they correct me, and we laugh, but it does worry me as these indexed power dynamics worm there way back into my vernacular.